研究者 > 西秋 良宏 > Nishiaki Lab. Top > Kosak Shamali

Tell Kosak Shamali, the Upper Euphrates, Syria

Yoshihiro Nishiaki

The University Museum, The University of Tokyo, Japan

The excavations

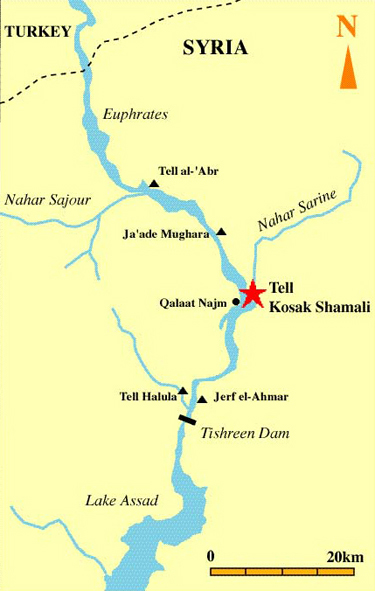

| Tell Kosak Shamali is situated at a strategic geographic position: it is on a terrace of the Upper Euphrates, cut by the Nahar Sarine, at the edge of the flood plain. In such a location, resources from different geo-ecological zones would have been readily available. In addition, the deep valley of the Nahar Sarine must have provided an excellent crossing point of the Euphrates, which even today makes the area important.

|

Fig. 2 Tell Kosak Shamali and the related sites in the Tishreen Dam area |

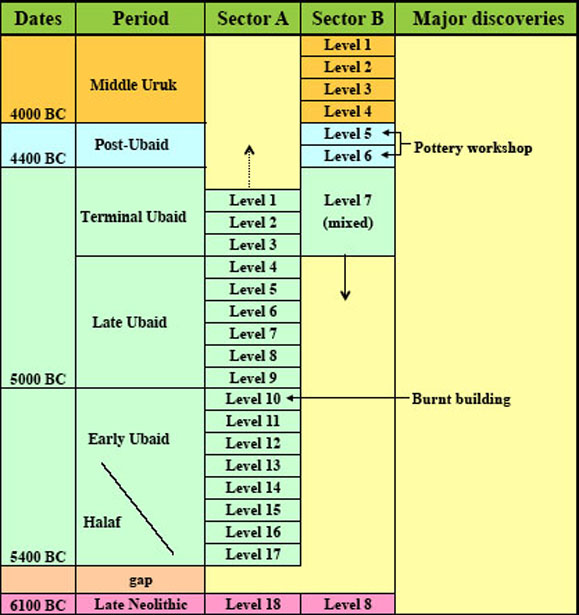

Scientific investigations at this prehistoric mound were conducted by the University of Tokyo team between 1994 and 1997, as part of the salvage

archaeological operations prior to construction of the Tishreen dam. The excavation of two areas revealed stratified settlements of the Neolithic to the

Middle Uruk periods, dating from the 7th to the 4th millennium BC. Among numerous discoveries, the most important was a series of pottery

workshops of the Ubaid and Post-Ubaid periods, including that preserved in an Ubaid burnt building. In the course of detailed analysis of those

workshops, the increasing social and economic complexity in these periods has come to light, which eventually led to the emergence of urban society

in North Syria.

Fig. 3 The Tishreen Dam area in 1993 |

Fig. 4 Tell Kosak Shamali seen from the southeast. The Nahar Sarine, presently dried up, runs in front from the right. |

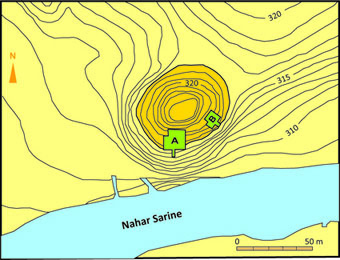

Fig. 5 The excavated areas of Tell Kosak Shamali (Sectors A and B) |

Fig. 6 Chronological table for the Tell Kosak Shamali occupational sequence |

Pottery workshop of the Ubaid period

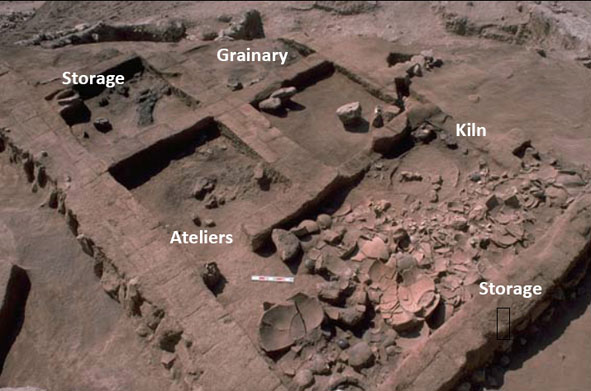

Level 10 of Sector A produced a large burnt building consisting of at least ten spatial units. Because of the fire the room floors were exceptionally

well-preserved, on which numerous ceramics, stone tools and other objects were discovered in primary contexts.

Fig. 7 Pottery manufacturing tools and facilities of the Ubaid period at Tell Kosak Shamali |

Fig. 8 The Ubaid burnt building of Level 10 of Sector A |

| Remains from the floor indicate this building complex to have been a pottery production workshop. Rooms 10A01 and 10A03, which contained over 150 and 20 complete pottery vessels respectively, were mainly used for storage of pottery. Room 10A01 was probably used for pottery production as well, as indicated by a kiln and potters' tools discovered in it. Rooms 10A02 and 10A05, which yielded numerous pottery production tools such as ceramic scrapers and stone palettes, were perhaps manufacturing rooms. The other rooms appear to have been grain storage. |

Organic materials were recovered from the burnt building in an excellent collection. An archaeobotanical analysis of the grain storage shows that

wheat and barley were stored separately in different rooms. The wheat included two-seeded einkorn, a species locally domesticated on the Upper

Euphrates. The charcoal samples derived from building materials consisted of taxa typically encountered in the gallery forest of the Euphrates. Poplar,

willow and alder were used for roof beams while tamarisk was used to cover the spaces between the beams.

Clay for pottery was obtained from banks of the Nahar Sarine and the Euphrates. It was then shaped into vessels on a slow turning table. Surfaces of

the vessels were smoothed with the use of stone polishers made on river pebbles, and possibly gazelle horns as well. Crescent-shaped ceramic scrapers

were also used for surface treatment. The main decoration method of pottery was painting. Natural crops of hematite and manganese, processed with

grinding stones and palettes, were used as pigments. The painted motifs were mostly geometric, but animals and birds were also depicted. Pottery was

fired in horse-shoe shaped kilns, and the vessels were piled in storage rooms for later distribution.

Pottery from the workshops often contained pairs or groups of pottery that display highly similar workmanship in size, decoration and manufacturing

technique. It suggests they were manufactured by a limited number of individuals.

Potters' workshops were discovered from many levels of the Ubaid period. One of the common features is that they overlapped traces of domestic

activities in the same building complexes, such as ovens, infant burials and grain storage. This undifferentiated use of similar structures for different

purposes may characterize the use of space in the Ubaid period, which is in clear contrast with that in later periods.

Fig. 9 Refitting the broken ceramics from the Ubaid burnt building |

Fig. 10 Part of the reconstructed ceramics from the Ubaid burnt building |

Fig. 11 Pottery with a snake and goat figurine inside from the Ubaid burnt building |

Pottery workshop of the Post-Ubaid period

Levels 6 and 5 of Sector B represent two episodes of the use of the same building complex, consisting of workshop structures for pottery production

and firing. Two large kilns, standing over 1.5 m high from the room floor, were the remarkable features. They allowed a mass production of pottery.

To the south there was a pottery manufacturing room in which a circular bin for clay preparation was installed. The pottery was dried in an area to the

east, and then brought in the kiln through a passage paved with mud-bricks.

The highly sophisticated workshops, located far from the domestic quarter, suggest the presence of specialized potters and more complex patterns

of pottery production and consumption in the Post-Ubaid period.

Pottery of the Post-Ubaid no longer included many painted vessels as in the Ubaid period, but most of them were simple plain wares. Firing was made

with a higher temperature using the developed kilns. Pottery production tools also showed changes from the Ubaid period. Ring-shaped scrapers joined

in the tool inventory, and stone palettes for pigment preparation, very common in the Ubaid period, virtually disappeared. For pottery shaping, faster

turning tables were used.

Fig. 12 The Post-Ubaid pottery workshop of Tell Kosak Shamali |

Fig. 13 Tell Kosak Shamali submerging in the Tishreen Dam Lake |

Further readings

- Nishiaki, Y. and T. Matsutani (eds.) (2001) Tell Kosak Shamali - The Archaeological Investigations on the Upper Euphrates, Syria. Volume 1:

Chalcolithic Architecture and the Earlier Prehistoric Remains. UMUT Monograph 1. Oxford: Oxbow Books. - Nishiaki, Y. and T. Matsutani (eds.) (2003) Tell Kosak Shamali - The Archaeological Investigations on the Upper Euphrates, Syria. Volume II:

Chalcolithic Technology and Subsistence. UMUT Monograph 2. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

西秋研究室トップ | Nishiaki Lab. Top | Tell Seker al-Aheimar | Tell Kosak Shamali | Tell Kashkashok II