研究者 > 西秋 良宏 > Nishiaki Lab. Top > The Middle Euphrates Survey Project, North Syria

The Middle Euphrates Survey Project, North Syria

Yoshihiro Nishiaki

The University of Tokyo

Introduction

Fig. 1 Location of the survey area and Tell Ghanem al-Ali |

Due to intensive investigations, notably salvage archaeological operations in the Tabqa and Tishreen dam flood zones, the Middle Euphrates Valley is extremely valuable for reconstructing the long history of human occupations in inland Syria. However, most investigations have been conducted in its narrow valley basin, leaving the archaeological record of its hinterland, which is dominated by the vast steppe, relatively unexplored. In an effort to better understand the human exploitation of the Syrian steppe in prehistory, a series of intensive archaeological surveys focused specifically on the steppe were conducted for five seasons between 2008 and 2011.

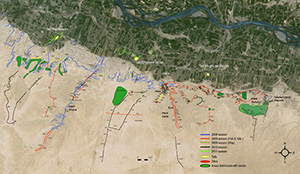

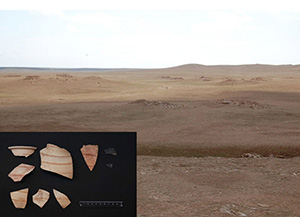

The surveys were conducted on the right bank of the Middle Euphrates, approximately 50 km east of Raqqa, North Syria, which nowadays enjoys annual precipitation of less than 150 mm (Fig. 1). The target area was the 10 km radius around the Early Bronze Age site of Tell Ghanem al-Ali, which was under excavation by a Syro-Japanese team, situated at the boundary of the valley basin and the steppe (Fig. 2). We navigated the steppe area using high-resolution satellite images and a compass. More than 200 archaeological sites and findspots were thus recorded (Fig. 3), enabling us to make a preliminary evaluation of the human occupations in the steppe from a long-term perspective.

Fig. 2 General view of the plateau and the lowland along the Middle Euphrates |

Fig. 3 The survey paths and the recorded archaeological spot |

Archaeological sites in the survey area

The surveys documented an extensive human history on the steppe from the Lower Palaeolithic onwards. Lower Palaeolithic artifacts, including Middle (Fig. 4) and Late Acheulean hand axes, were collected mainly from the ancient gravel layers of the Euphrates. On the other hand, Middle Palaeolithic and later materials were discovered, often in primary contexts, on the steppe. The area with the densest distribution of lithic artifacts was along the Wadi Kharar. This was one of the largest wadis in the survey area with water flows even in summertime, at least in parts. Moreover, it was distinct because of its length (ca. 20 km) and its well-developed terraces, while the other wadis in the survey area stretched a few kilometers in length at most. A number of Middle, Upper, and Epipalaeolithic findspots were located on the terraces of this wadi, and important discoveries included assemblages from the Early Ahmarian of the Upper Palaeolithic (Fig. 6) and the early Middle Epipalaeolithic (Fig. 7), which are rare in the northern inland Levant. However, the Late Epipalaeolithic and the early Neolithic sites were missing in our records, although sites from these periods have been well recorded at the edge of the valley basin, such as at Tell Abu Hureyra and Tell Mreybet.

Fig. 4 Lower Palaeolithic, Zor Shamar (Site 10BF) |

Fig. 5 Middle Palaeolithic, Wadi Kharar (Site 16M) |

Fig. 6 Upper Palaeolithic, Wadi Kharar (Site 16R) |

Fig. 7 Epipalaeolithic, Wadi Kharar (Site 16K) |

The next period represented by the surveyed sites was the late Neolithic. Although all of these were aceramic, the typological features of the collected lithics indicate a Pottery Neolithic date, probably the 7th millennium BC (Fig. 8). They likely represent temporary camps for herding or hunting. Similar observations were also made for the Chalcolithic sites, which yielded flint scatters but no ceramics (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8 Neolithic, Jazla West (Site 23BJ) |

Fig. 9 Chalcolithic, Wadi Mugla (Site 15C) |

Fig. 10 The early Middle Bronze Age settlement of Tell Jazla East (23H) |

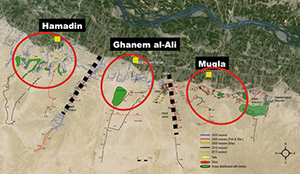

On the other hand, archaeological sites from the Bronze Age show dramatic changes in site characters. They consisted of at least four types: long-term occupations, transitory camps, flint quarry sites, and cemeteries. Long-term occupations were represented by the lowland, Early Bronze Age tell-based settlements at Tell Ghanem al-Ali, Tell Hammadin, and Tell Mugla as-Saghir as well as the early Middle Bronze Age mound of Tell Jazla East, which was located at the edge of the steppe (Fig. 10). The transitory camps were defined by aceramic flint scatters (Fig. 11), while flint quarry sites were identified at exposures of the ancient gravel layers in the steppe (Fig. 12). Cemeteries were defined by clusters of tombs, which consisted of a variety of types including shaft tombs (Fig. 13) and cairns/mound tombs with stone chambers (Fig. 14).

Fig. 11 Flint scatters of the Early Bronze Age, Wadi Shabout East (Site 20A) |

Fig. 12 Flint quarry of the Early Bronze Age, Wadi Beilune (Site 27AD) |

Fig. 13 Shaft tombs of the Early Bronze Age, Wadi Jazla East (Site 23I) |

Fig. 14 Cairn fields of the Early Bronze Age, Beilune (Site 27L) |

Bronze Age settlement pattern in the steppe

On the whole, the most impressive characteristic was the radical change in the settlement pattern at the onset of the Bronze Age. The increase in the number of sites during this period was probably exaggerated by the presence of tell-based sites and cemeteries, which retain greater visibility for surveyors due to the associated ceramics. However, even when excluding tell-based sites and cemeteries, the large number of aceramic flint scatters assigned to the Bronze Age (Fig. 15) is obviously a marked contrast to the low number in comparable sites from the previous periods. Our detailed analysis of the lithic artifacts indicates that the sharp rise of flint scatters occurred in the late stage of the Early Bronze Age (Fig. 16); it is strongly suggested that the exploitation of the Middle Euphrates steppe started in this period on a hitherto unparalleled scale.

Fig. 15 Early Bronze Age flint artifacts from Wadi Shabout East (Site 20A) |

Fig. 16 Results of a correspondence analysis of flake platform types. Periodization is possible based on the technological traits of the flakes from the aceramic flint scatters in the steppe. |

Fig. 17 Three lowland Bronze Age settlements and their burial grounds on the plateau |

This pattern is quite indicative of the supposed development of tribal society based on the pastoralist economy during the Early Bronze Age. Careful examination of the survey data revealed three major Early Bronze Age settlements and their corresponding cemeteries on a plateau (Fig. 17). Importantly, these pairs were separated from one another by areas comprised of deep wadis that lacked burials; this pattern suggests that the groups occupying these settlements and to which the burial grounds might have belonged mutually respected geographical boundaries and maintained their own territories, most likely reflecting a certain level of tribal structure. These communities, who intensified the steppe exploitation in the late Early Bronze Age, abandoned the lowland settlements from the early Middle Bronze Age and established new settlements at the edge of the steppe, as documented at Tell Jazla East. Our surveys did not identify later settlements, although plenty of cemeteries have been recorded from the inland Bishri Mountains to the south. The survey data, although from a limited geographic area, should certainly reflect important settlement dynamics that occurred from the Early to Middle Bronze Age in the Middle Euphrates Valley, which need to be further analyzed on an interregional scale as this period has been known to have witnessed important socio-economic changes in varied regions of Mesopotamia and beyond.

References

- Kadowaki, S., T. Omori and Y. Nishiaki (2015) Variability in Early Ahmarian technology and its implications for the model of a Levantine origin of Protoaurignacian. Journal of Human Evolution 82: 67-87.

- Kadowaki, S. and Y. Nishiaki (2015) New Epipalaeolithic assemblages from the middle Euphrates and the implications for technological and settlement trends in the northeastern Levant. Quaternary International (in press)

- Nishiaki, Y. (2010a) Archaeological evidence of the Early Bronze Age communities in the Middle Euphrates steppe, North Syria. Al-Rafidan Special Issue, Formation of Tribal Communities -Integrated Research in the Middle Euphrates, Syria: 37-48.

- Nishiaki, Y. (2010b) Early Bronze Age flint technology and flake scatters in the North Syrian steppe along the Middle Euphrates. Levant42(2): 170-184.

- Nishiaki, Y. (2014a) Steppe exploitation by Bronze Age communities in the Middle Euphrates Valley, Syria. In: Settlement Dynamics and Human-Landscape Interaction in the Steppes and Deserts of Syria, edited by D. Morandi Bonacossi, pp. 111-124. Studia Chaburensia 4. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Nishiaki, Y. (2014b) Dating simple flakes: Early Bronze Age flake production technology on the Middle Euphrates Steppe, Syria. Journal of Lithic Studies 1(1): 197-212. doi:10.2218/jls.v1i1.781

西秋研究室トップ | Nishiaki Lab. Top | Tell Seker al-Aheimar | Tell Kosak Shamali | Tell Kashkashok II

The Middle Euphrates Survey Project